This is the third in a series of articles which examine the internal and external factors which, when taken into consideration, will indicate the preferred model for procurement within a business.

In the first article, I concentrated on the purpose of Procurement, setting out 10 business objectives which sit on the price-down-to-value-capture continuum (i.e. price down, cost down, cost out… value creation and value capture), from purely tactical to highly strategic. I concluded that fully mature procurement and centralisation are in conflict.

The second article proposed 5 dimensions to be considered in designing procurement organisation:

- Corporate coherence

- Procurement maturity

- Homogeneity of requirements

- Supply market opportunity

- Category integration into the value chain

Before examining component factors, It might be helpful to examine how, within a specific business, the business strategy influences the connection between the 5 dimensions, and the role and purpose of Procurement.

Business Strategy

- at one extreme retrenchment and recovery, requiring a tactical cost-down approach to procurement;

- at the other extreme, a prospective, high-growth strategy, requiring procurement to focus on supply chain transformation, innovation and value capture;

- in between, a range of business protective and business improvement strategies, requiring procurement focus on supplier, product and process improvement.

Within the broad, middle ground, business value propositions may be based on cost leadership or differentiation, requiring procurement to focus either predominantly on cost down/cost out or on value creation. And even in recovery situations a traditional turnaround approach, based on rationalisation and cost-cutting, may give way to a more progressive transformational approach involving outsourcing and restructuring of supply chains.

Corporate Coherence

The structure and organisation of the corporation, the relationship and synergy between business areas, corporate history, culture and politics, all have a substantial influence on the effectiveness of procurement options.

Different parts of the corporation may well be in different stages of their business life-cycle and may be pursuing opposing business strategies (e.g. BCG Matrix and relevant strategies). The history of the corporation, whether it has grown organically, or by acquisition and merger will influence the extent to which different parts of the operation work together. A culture of co-operation and co-ordination, or of relative autonomy, may not necessarily reflect the official organisation structure. For example, even within SBUs, individual sites may be autonomous profit centres with little functional support from the SBU centre.

In addition to these ‘soft’ constraints there may be considerable barriers to the sharing of information according to the ICT infrastructure within and across the businesses (i.e. at a more fundamental level than procurement applications that may be necessary to support particular models). Consequently, after compatibility of procurement’s purpose across the SBUs has been established, the general systems and ways of working need to be taken into account.

Procurement Maturity

The different SBU strategies within the corporation will confer different expectations and corresponding differences in the requirement for procurement maturity.

Aside from the possibility that an SBU may have an over-skilled and underutilised resource, any new procurement organisation (or re-organisation of existing resources) will need to match, or improve on the existing capability, otherwise existing management will be reluctant to give up control. The greater the maturity of existing procurement, the greater the challenge. Although procurement may be classified as a support activity, it may be highly integrated into the value chain and difficult to separate without causing substantial damage.

The relative integration of different categories of purchases will be covered later in this article. At this point I am referring to the general maturity of the procurement function in the context of the SBU’s objectives on the price-down-to-value-capture continuum, as determined by the SBU strategy.

Any new structure needs to take into account any enhancement or degradation of capability arising from any relocation or change in reporting lines consequential to the new structure.

Homogeneity of requirements

The homogeneity, or rather the lack of homogeneity, can take different forms.

- different raw materials: plastic mouldings vs. metal fabrications

- different services: local small parts distribution vs. international bulk liquids transport.

- textiles: mass market garments vs. high fashion

- intercontinental shipments: low cost (ocean freight) vs. agile (air freight)

Whilst both sets of examples are obvious mismatches, there are many examples of subtle but irreconcilable differences that are not apparent without detailed knowledge of materials, technology, channels to market, customer segmentation, applications environment, etc.

A reasonable appreciation of the homogeneity of requirements is a prerequisite to determining procurement organisation. It would be naive to create an organisation on an assumption that corporate leverage follows from pooling requirements.

Supply Market Opportunity

Even when there is homogeneity of requirements across SBUs, there may not be the supply market structure to service pooled requirements.

Global supply markets exist for relatively few basic commodities and high-value products and services. Many global supply opportunities are illusory – air flights, cars, ‘commodity’ plastics, energy, for example – so businesses that operate within different regions may have little opportunity for collective purchasing. Some of the constraints are down to different supplier focus and strategy (a lack of uniformity in product and sector focus across regions) others down to a complete absence of suppliers with the required geographic spread. Opportunities for ‘globalisation’ generally come down to low-cost country sourcing for wider geographic consumption, or use of high-value service providers that operate internationally.

Category Integration into the Value Chain

In the first article, I introduced the concept of 10 business objectives on the price-down-to-value-capture continuum. I have also referred to the support activities and primary activities within the value chain. Purchased inputs are present in every activity, be it support or primary, value activity.

Some categories of purchases are only required for support activities; others may be required for value activities but only contribute to cost competitiveness, not to differentiation. Some may be the very essence of value creation. So the capability of goods, services, and their suppliers, to impact on value creation varies from inconsequential to essential.

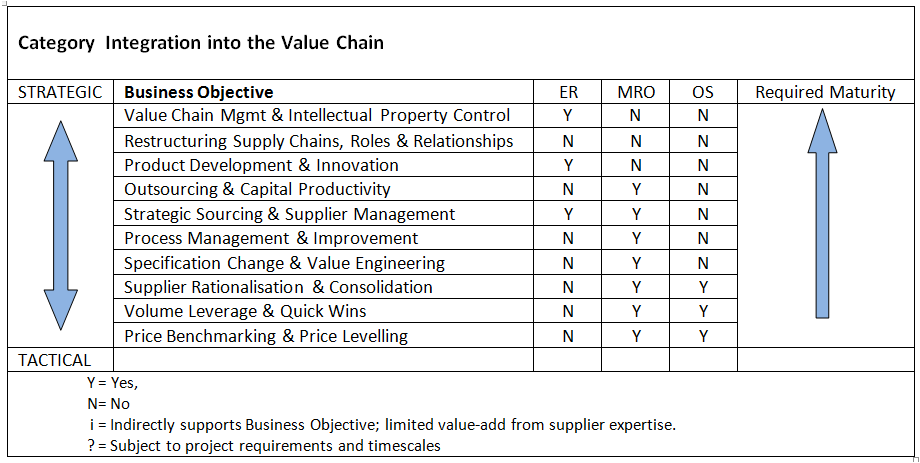

Now it is possible to map categories over the 10 business objectives in terms of their potential impact. Consider three categories for a technology company – extramural research (ER), maintenance repair and operations (MRO), office supplies (OS) – as shown in Table 1.

Extramural research may be critical to a specific value creation and value capture opportunity, say in connection with finding a way around competitor’s patent to develop a new product. There may be no connection at all with supply chain construct or process improvement, and no relevance to supplier consolidation and volume leverage.

At the other extreme, office supplies have virtually no real relevance to value creation; procurement considerations are entirely about minimising cost and effort consistent with acceptable quality and service.

MRO falls between the other two categories in the sense that there may be opportunities to rationalize suppliers and exploit leverage, but also significant gain from reducing maintenance costs, downtime, and parts inventory. The potential for integration with value chain is high in that MRO could include outsourcing of essential maintenance services. So a compromise has to be reached between (a) organising for highest value – managing procurement for each value chain, or (b) lowest cost – managing procurement across multiple value chains.

Conclusions

The considerations necessary for design of an effective procurement organisation are complex. There are 5 dimensions to be considered. Each dimension raises searching questions about the specific nature of the business and its unique circumstances. It would be convenient if this array of considerations could be resolved into a simple 2-dimensional or 3-dimensional model. Can it be done? That will have to wait for a future article.