A recent discussion with procurement consultant, Bill Young, caused us to reflect on the use of ‘supply positioning’ as a model for developing strategies to add value through procurement. We considered the possibility of positioning procurement projects rather than purchase items or supply categories. I concluded that this application had potential but also had practical difficulties. The use of supply positioning by Procurement, without the engagement of other stakeholders, is dangerous. As supply positioning is often misapplied, I thought I might share my thoughts here.

Most procurement professionals will be familiar with a number of 4-quadrant ‘supply positioning’ models. The original and (probably) most widely used is Kraljic’s Purchasing Portfolio matrix (1983), which plots profit potential against supply vulnerability. Subsequent variants have been developed, for example Elliott Shircore & Steele’s Procurement Positioning (1985), and Van Weele’s Purchasing Portfolio (2000).

The models are frequently misused. I have, in an article “How to select suppliers to create value,” commented on inappropriate use in ‘supplier positioning’.

Supply positioning models convey important concepts but have significant weaknesses in their practical application:

- They are intended for purchase items or categories; suppliers and projects may span more than one quadrant (as indeed may categories).

- They pose unanswered questions about exactly what will be positioned, at what level of aggregation, and for what organizational unit will the analysis be performed.

- The supplier’s side of the supplier/buyer relationship is disregarded. For projects, the sponsor’s (and other stakeholders’) requirements need to be taken into account.

In practice, if you perform a portfolio analysis on individual supply categories you will often identify component groups that map across different quadrants of the grid; then when you look within component groups you may find individual items sit in different quadrants; different mappings are generated with different operating units, and so on. So although supply positioning models are informative in terms of an overview, they do little to connect specific critical issues and opportunities either to broad categories or supplier capability.

Casual use of supply positioning models by Procurement can easily lead to the development of a general category strategy that fails to address critical issues – a possible cause of procurement initiatives failing to deliver to the bottom line. We need therefore to look to other approaches for the identification of critical issues. The perspective of other stakeholders is crucial.

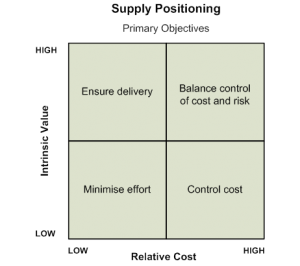

I’ve created a matrix (Figure 1) of intrinsic value (as value is what we are ultimately trying to deliver) v. relative cost, which I use to

- perform item/category analysis from an operational perspective – first making a general assessement of the category and then looking for exceptional items or sub-categories.

- link to Value Chain Analysis (VCA) for strategic and supplier perspectives.

Both supply positioning and VCA are carried out by cross-functional teams.

‘Intrinsic value’ is a composite measure of opportunity (to be exploited) and risk (to be mitigated) to satisfy customer needs and a firm’s strategic initiatives to secure competitive advantage. The composite measure allows a simple 2-dimensional grid and a matrix that reflects the trade-off between cost and value.

Intrinsic value is a concept that can be applied to projects; the more problematic axis is “cost”. The model (as shown) does not make sense if we use project execution cost. We might be interested in the impact a procurement project might have across the purchases portfolio, in which case “cost” is the relative cost of the affected items/categories.

When considering the value to be gained from procurement projects, Bill Young suggested that we might identify the relevant project drivers:

- input drivers – cost/price

- output drivers – utility (what the customer is prepared to pay)

- strategic drivers – for example, proprietary innovations to gain competitive advantage or access to new markets.

The purpose of this is to disaggregate the benefits in order to see each clearly.

Bill’s approach is consistent with VCA guru Michael Porter’s sources of competitive advantage (cost advantage and differentiation) and definition of value (“the amount that buyers are willing to pay for”) and my own. The separation of ‘utility’ and ‘strategic’ drivers may help to stimulate cross-functional debate, although strategic initiatives are aimed, ultimately, at either reducing cost or improving value to the customer (or a complex combination of the two, often with a view to future customers and markets).

The cross-functional debate, and the identification of opportunities, risks, costs and benefits, is more important than accurately positioning a project, item or category on a grid. Supply positioning is not a tool to be used unilaterally by Procurement. The positioning of a category comprising ostensibly similar items and creation of a one-size-fits-all strategy is inherently dangerous. Generic category strategies derived this way are likely to have unforeseen consequential costs or damage to the business. In terms of the entity to map, the most important attribute is its homogeneity. Robust analysis by a suitably informed team is necessary to identify anomalies and exceptions.

Related Articles:

- How to Start a Strategic Value-Added Programme

- How to select suppliers to create value (Introduction)

- How to select suppliers to create value: Supplier Appraisal

- How to Select Strategic Suppliers – Part 1: Beware the Supplier’s Perspective

- How to Select Strategic Suppliers – Part 2: Reconciling Buyer and Supplier Perspectives

I will appreciate a write up on supply positioning tools

Try the two posts, Parts 1&2 of “How to Select Strategic Suppliers….” – follow links at the foot of this article.