12 Tips for fmcg and food industries

This is the fifth in a series of articles on how to implement and enhance a gate process (also known as stage gate process). The series sets out to highlight some of the issues associated with the introduction and operation of gate processes, and to offer some advice in the context of consumer products.

One of the reasons for writing this series is that much of the literature seems to be more aligned to engineering and technology products than to my interests, which are primarily food and fast-moving consumer goods.

In Part 1, I defined my scope as “the application of gate process as a key element of product portfolio management, and the process between gates (the stages) as well as the gates themselves.” I gave a brief history of the gate process, the goals and benefits, and a list of issues that are symptomatic of a badly designed or badly implemented process, or are frequently encountered where no gate process exists.

In Part 2, I commented on the first steps in setting up gate process, or sorting out one that has significant issues: stakeholder engagement; mapping existing processes; project management for the gate process implementation.

Part 3 and Part 4 covered the basic design and operation of the stages and the gates.

In this article I will cover some specific fmcg and food industry issues: 12 things to look out for, together with my tips for improving control of costs and timely project delivery.

Fmcg and food industry gate process issues

In the last article I referred to reports in The Grocer and Just-food.com that fmcg and food new product developments have only a 20% success rate and the cost of innovating is rarely covered.

A well designed and operated gate process may not guarantee success, but it will ensure the early kill of weaker projects so that resources can be focused on those with the greater probability of success. It will also control development costs, which is often not a high priority concern of marketeers.

There are a number of specific issues relevant particularly to fmcg and food industries which can result in excessive and avoidable development costs. Here are my tips on 12 things to look out for, and what to do about them:

1. Control responsibilities

NPD and launch process is often controlled by Marketing. Marketing may be the best function to lead ideation, but not subsequent activities. The characteristics that make a good marketeer do not necessarily (or generally) make a good project manager. Objective assessment and reassignment of control responsibilities may be required.

Preferred practice is to have an independent change control function to oversee the projects portfolio and manage project managers.

2. Timing of decisions and approvals (and other deliverables)

Compared to fmcg, engineering and technology industries seem to have wider appreciation and respect for the critical path. It is essential to address any Stakeholders’ and gate keepers’ inability to recognise that delaying critical path activities directly impacts on the timeline. This includes senior managers!

Delays at gates can lead to substantial slippage: just a few days at each gate can add up to a month’s extension to the overall timeline. It is important that routine approvals do not wait for portfolio review meetings; these are to deal with exceptions.

Correct sequencing of decisions is also important. A common failing is to set launch dates before feasibility is assessed, which usually results in unrealistic and unachievable timelines.

3. Specifications

Failure to lock specifications at an appropriate time can allow further unscheduled iterations in the design process. Late changes in specification must be prevented to avoid consequential implications for

(a) statutory declarations (contents, allergens) on packaging,

(b) shelf-life testing (where required).

4. Shelf life tests

Although not necessary for many products, where shelf life testing is required, re-tests can be both a cause and consequence of specification changes. This can be problematical with some foods where the test cycle is on the critical path and accounts for a relatively high proportion of the overall development time. In such instances, consideration might be given to parallel testing of a number of possible variants rather than sequential testing. This reduces the risk of having to re-test. Whilst this approach might appear to create additional work, the cost may be more than offset by improved workflow across the whole project portfolio.

5. Bespoke materials

Limited-use and bespoke materials need close attention. These may be high risk in terms of potential redundancy, or availability if product demand exceeds forecast. Late killing of projects, after materials have been ordered, can result in large cost write-offs. Timing of the procurement cycle to guarantee availability is also critical. Early visibility of requirements, to allow sourcing to commence, and commercial terms to allow flexibility, can substantially reduce both development time and risk.

6. Packaging

Retail packs are usually bespoke and (together with some other packaging) need similar consideration to bespoke materials. There is usually the additional complication of print design (covered by the next item).

7. Design and reproduction

Design and repro are a perennial cause of conflict in some fmcg and food businesses. The problems arise if the design is not locked before moving to repro, adding both time and cost of rework. In worst cases, I have witnessed design changes (for aesthetic rather than statutory reasons) after gravure cylinders have been engraved… a costly iteration which probably had minimal impact on customer appeal and ultimate success or failure of the product. It can become habitual to make late changes. Even though design and repro are usually on the critical path, I would recommend a gate between (Gate 4 in the example provided in Part 4).

8. Product redundancy

Product redundancy is an issue when a launch bombs. Redundancy also occurs when product substitutions are not synchronized. Product run-down and launch synchronization needs to be built into the stage gate process. Plans need to take account of bespoke materials and packaging supplies as well as manufactured product. Attention to forecasting and supply chain agility are key elements of risk mitigation and cost control.

9. Forecast inaccuracies

Just-food.com reports that promotions were “key” to the success of product developments. The unpredictability of demand from promotional activity is always a challenge for supply chain managers and can give rise to enormous wastage or shortages. Opportunities to develop agile supply strategies may remain untapped. I have covered this at length in two articles on forecasting: “The mess businesses get into” and “Products at risk, and managing inbound supply“.

10. Systems

Information systems to support stage gate process is far too large a topic to cover here. Suitable systems need not be complex or expensive; much can be achieved with off-the-shelf software (e.g. Lotus Notes or Sharepoint).

Critical requirements are as follows:

- Systems must provide real-time visibility of status, i.e. deliverables completed.

- By using templates the differing requirements of branded, generic, customer-branded, licensed or outsourced products can be accommodated – as can NPD, EPD and other suitable business change projects (covered in Part 2).

- Electronic approvals will minimize delays pending approval.

There is generally no need to create workflows for all activities within a Stage. For fmcg and food product developments, I would aim for maximum flexibility/agility and minimum bureaucracy within stages.

11. Scheduling

Careful delineation of sub-processes allows three things to happen:

(a) sub-processes can be functionally-led, i.e. responsibilities for individual sub-processes can be assigned to individual departments or functions;

(b) the activities within sub-processes are performed by departmental members or by a cross-functional cell controlled by the lead function;

(c) timelines can be tracked at sub-process level, and activities within each sub-process can remain unscheduled; each cell or department manages its own workload.

In most cases, stamping each deliverable with time, date and signature is sufficient to generate process KPIs and maintain control.

12. Process metrics

In addition to tracking the progress and performance of individual projects, the overall performance of the process needs to be tracked. The intention here is to identify repeat constraints, or systemic problems with the process, with a view to further improvements.

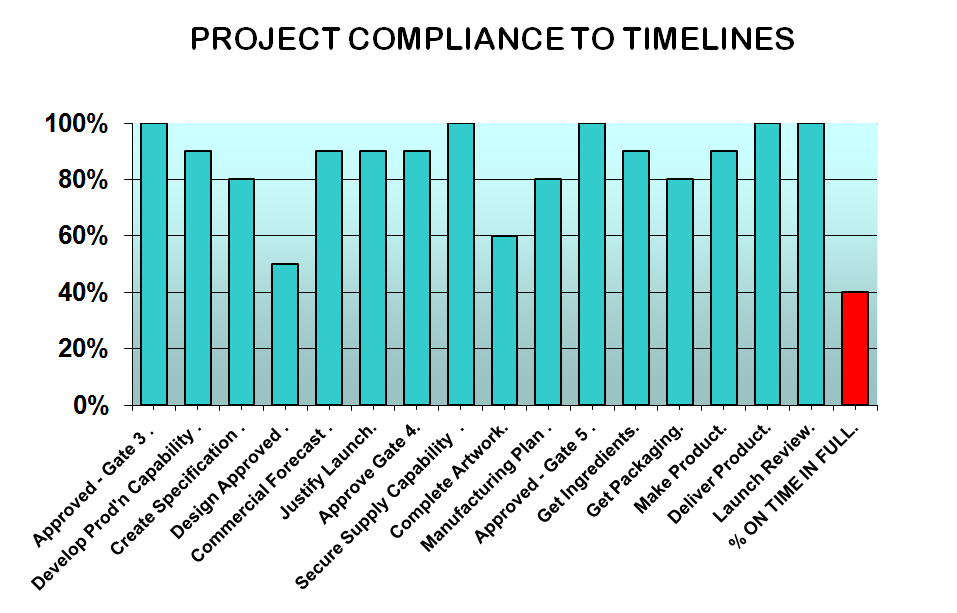

In the example presented in Part 4, provisional timelines were set in Stage 2 prior to formation of the project team. The timeline is then updated by the project team in Stage 3 as they complete their plan. This planning puts timings to pre-determined milestones (the completion of sub-processes) used for tracking project delivery. Process performance can then be measured by monitoring compliance to timelines over a number of projects. An example is shown in Figure 1. (Note: this corresponds to the example flow diagram at sub-process level depicted in Part 4, Figure 2)

Similarly, it would be possible to track cost variances by sub-process to establish which sub-processes are regularly generating cost overruns.

The combination of the approach to (minimal) scheduling in item 11, and the process metrics in item 12, above, allow application of the Theory of Constraints. If deliverables are date stamped, it very easy to track which activities within stages are regularly holding up completion of the stages. Tagging deliverables with the signature of the responsible team member allows traceability back to departments, functions or individuals so that constraints can be identified and investigated, and improvements made.

Where next?

The next article, the last in the present series, will summarize the five previous articles and provide a few additional tips. Hopefully this will provide a handy quick-reference guide on how to implement and enhance a gate process.

Related Articles:

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 1

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 2

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 3

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 4

- Overcoming obstacles to successful change programmes

- A single shared forecast for the business… so what’s the problem?

Part 1: The mess businesses get into

Part 2: Products at risk, and managing inbound supply