Few customer-supplier partnerships are equal. Buyers need to be wary of entering into dependent relationships where the supplier will gain a dominant position. This is the first part of a 2-part article which sets out to examine how and why Procurement might consider the supplier’s perspective when selecting suppliers. It is particularly relevant for strategic supplies, where value creation and value capture are key objectives.

In researching published approaches to determining procurement organisation, and in a series of discussions with procurement professionals on LinkedIn, I have gradually come to realize that surprisingly little reference is made to supply market constraints and the willingness (or otherwise) of suppliers to do business. The connection between procurement organisation and selecting suppliers to add value is that the historic focus of procurement organisation has, in my opinion, been directed at cost-down rather than value-adding initiatives.

The focus of the LinkedIn discussions, in particular, “Is centralised procurement past its sell-by date? What alternative model would you suggest, and why?” has been canvassing opinion on whether that historic focus needs to change. Appreciation of the significance of the suppliers’ perspectives perhaps needs to be tested, but I am reminded of an optimistic vision… an image of suppliers queuing up, falling over themselves to do business, and where the buyer is in control… an image too often reflected in procurement practices, not least in the public sector where mandated practices are heavily reliant on a pre-existing competitive supply market.

Many procurement professionals will be acutely aware that fervent supplier interest is not always present. Small businesses often suffer a lack of interest from potential suppliers. Medium-sized groups may find themselves unable to gain any traction on what, at first glance, might seem to be volume-leveraged opportunities. Even large companies may occasionally find that their size works against them in the sense that suppliers may be wary of the commitment and vulnerability associated with putting ‘too many eggs in one basket’. Research into strategically important categories reveals, when suppliers are ready and willing, more often than not, it is they who have the upper hand.

So, for many categories, the supplier’s perspective warrants investigation. How do we do this?

Purchasing Portfolio Analysis (a.k.a. Supply Positioning)

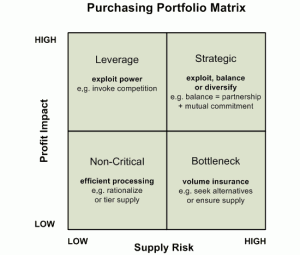

Most purchasing professionals will be familiar with purchasing portfolio analysis, using, for example, Kraljic’s Purchasing Portfolio matrix (1983), which plots profit potential against supply vulnerability (Figure 1).

I have previously commented on Kraljic and similar matrices with regard to the significant weaknesses in their practical application to supplier appraisal. Supply positioning models nevertheless convey important concepts, notably the differentiated purchasing strategies for different segments of the portfolio. Together with other tools (e.g. PESTLE and Porters 5 Forces) they provide the foundations of category strategy.

Kraljic proposed three strategies for strategic items (exploit, balance or diversify) based on the relative power of buyer and supplier. Other subsequent 4-quadrant ‘supply positioning’ models (e.g. Elliot Shircore & Steele’s Procurement Postioning (1985), and Van Weele’s Purchasing Portfolio (2000)) have attempted to resolve the strategies to a single approach for each quadrant. Reviews by Dubois and Pedersen (2002), and by Caniëls and Gelderman (2005) compare various models.

Gelderman and Van Weele (2003) proposed strategic directions for all quadrants: within the ‘strategic’ quadrant, the choice is to find a new supplier, accept the locked-in ‘partnership’, or maintain strategic partnership, refecting Kraljic’s strategies ‘exploit’, ‘diversify’ or ‘balance’.

Digressing slightly from the main thrust of this article, it is worth noting that Gelderman and Van Wheele concluded that it is not possible to deduce strategies from a 2-dimensional portfolio analysis. Other factors need to be considered:

- the overall business strategy (related situations on end markets),

- the specific situations on supply markets, and

- the capacities and the intentions of individual suppliers.

“Unquestionably, the supplier’s side should be included in any strategic thinking on the field of purchasing and supply management.”

Caniëls and Gelderman examined the relative power and interdependence of supplier and customer. Where they expected to find a balance of power within the strategic quadrant, they actually found that supplier dominance prevailed. This suggested a disproportionate raise in the dependence of the buyer on the supplying partner once entering into partnership.

These sources provide a compelling case, still valid today, for Procurement to place particular focus on the circumstances and outlook of the supplier. One of the ways of doing this is by account portfolio analysis from the supplier’s perspective.

Account Portfolio Analysis (Supplier Perspective)

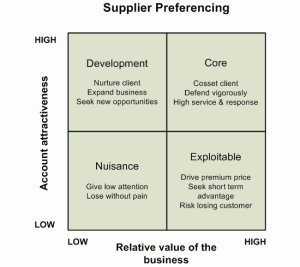

Most category managers will be familiar with Steele & Court’s (1996) Supplier Preferencing analysis (Figure 2) derived from earlier concepts in Key Account Management. This plots account attractiveness (to the supplier) against relative value (e.g. percentage of supplier’s gross margin or revenue).

This is a relatively simple analysis which takes no account of the dynamics of the supplier’s circumstances. Although satisfactory for tactical procurement, supplier preferencing is not a suitable tool for strategic category management. A fundamental weakness is that it offers no insight, and no response, to the future development or unsustainability of relative value. For example, might the present offering be under competitive threat? From the buyer’s perspective it would be undesirable to enter into a strategic relationship with a supplier whose capability is about to be overtaken by competitors.

A deeper insight may be gained by use of other portfolio tools such as the 4-quadrant directional policy matrix (DPM) or the 9-cell McKinsey/GE strategic business matrix, and the ADL portfolio management matrix.

Whilst there is merit in considering a supplier’s business strengths and weaknesses relative to the supply market, and its competitive position, the exercise can become complicated and potentially misleading. Our interest as buyers may be in relatively narrow products or technologies rather than the suppliers overall business portfolio. In any event we are generally going to be ‘second guessing’ the supplier’s view.

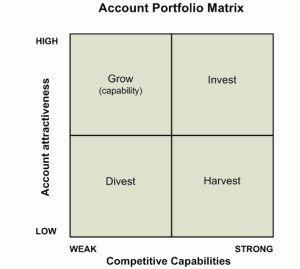

A better approach may be to undertake a less comprehensive assessment and then appraise the supplier by alternative methods (which I shall come to in part 2). A hybrid of supplier preferencing and DPM (Figure 3) plots account attractiveness against supplier’s capabilities relative to competitors, bringing into consideration factors that may drive a change in the relative value of the business.

The criteria for measuring account attractiveness and supplier’s capabilities are business specific. McDonald’s “12 steps to key account management portfolio analysis” contains an adapted version of the directional policy matrix, explains how this can be used to classify possible competitive environments and their respective strategy requirements, and includes factors used to determine account attractiveness and business strength. Readers may find these factors of interest, with particular regard to how they might influence and condition suppliers, with the intention of either changing or exploiting the supplier’s position and direction.

I started this article with a statement that few supplier-customer partnerships are equal, and a warning with regard to entering into relationships where the supplier might gain dominance. In the second part I consider how we can combine customer and supplier portfolio analyses to differentiate suppliers with potential for a balanced relationship from those that are likely to become dominant.

Related Articles:

Supply positioning is an interesting approach to purchasing strategies for different segments of the portfolio analysis.I’d be really interested into looking at a case study for further information. Definitely something I will take into consideration. I never thought of using portfolio strategically.

Please I want to know the strengh and weaknesses of the supplier positioning model.

I suggest you read the comprehensive review by Caniëls and Gelderman, and my earlier comments. Just follow the links in the article.

The main strength, and weakness, of the model is its simplicity. Gelderman and Van Weele explain why they set out to improve on the original Kraljic model – well worth reading if you are looking to use supply positioning as a strategic category management tool.