This is the second in a series of articles which examine the internal and external factors which, when taken into consideration, will indicate the preferred model for procurement within a business.

A discussion has been running in the Procurement Professionals Group on LinkedIn to explore why do centralised procurement initiatives often promise substantial savings, then fail to deliver to the bottom line? Apart from historically falling short of expectations, we are facing new issues such as increasing emphasis on corporate social responsibility and sustainability. The discussion prompted me to write a short article setting out 5 models for procurement organisation and start another discussion, “Is centralised procurement past its sell-by date? What alternative model would you suggest, and why?” For this latest discussion I suggested, irrespective of what worked in the past, we should focus on what will work in the future.

In the first article, I concentrated on the purpose of Procurement, setting out 10 business objectives which sit on the price-down-to-value-capture continuum (i.e. price down, cost down, cost out… value creation and value capture), from purely tactical to highly strategic. I concluded that fully mature procurement and centralisation are in conflict.

This article proposes 5 dimensions to be considered when designing a procurement organisation.

Various models for procurement portfolio analysis are sometimes used (incorrectly) to inform decisions on procurement organisation. It may seem that strategic categories are candidates for a centralised approach but to associate “strategic” with “centralised” is erroneous:

- Business strategy is generally formulated within strategic business units (SBUs).

- Attempts to impose overarching control of procurement in corporations comprising more than one SBU are bound to create conflicts.

- Resolution of these conflicts by top-down mandate will not lead to sustainable performance improvements.

- The greater the autonomy of the SBU’s the greater the difficulty in creating a coherent centralised approach.

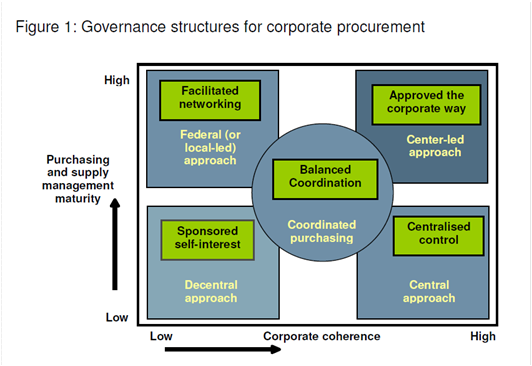

Following extensive research with large Dutch companies, Frank Rozemeijer (Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, 2000) proposed a set of 5 rules for the design of purchasing organisation for competitive advantage. Each of the 5 rules relates to an organisation approach according to the corresponding levels of purchasing maturity and corporate coherence (i.e. the extent to which the different parts of the corporation operate and are managed as one entity). The resultant 2-dimensional matrix (revised 2007) is in Figure 1.

Rozemeijer’s research highlighted the significance of corporate organisation and culture in determining purchasing organisation.

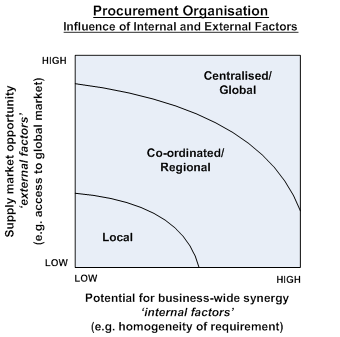

The research focused mainly on internal factors and, whilst taking into account the competitive forces in served markets, did not investigate the opportunities and constraints on the supply side. Nor did it specifically evaluate the global vs. local dimension.

In order to pursue the aggregation of local demand there needs to be potential synergy across the corporation, and the supply market has to afford the opportunity. To establish the form that procurement might adopt, we need to evaluate the constituent internal factors and external, supply market factors. The greatest constraints exist when business units have dissimilar requirements and a dependency on local supply. The greatest freedom exists when the requirements are homogenous and the supply market is global. This is represented in Figure 2.

- Procurement maturity

- Corporate coherence

- Homogeneity of requirements

- Supply market opportunity

- Category integration into the value chain

In Part 3, I comment on these dimensions in more detail.

Related Articles:

- 5 Models for procurement organisation

- How to Determine Procurement Organisation – Part 1: 10 Objectives for Procurement

- How to Determine Procurement Organisation – Part 3: The 5 Dimensions in Detail