Designing and operating the gates

This is the fourth in a series of articles on how to implement and enhance a gate process (also known as stage gate process). The series sets out to highlight some of the issues associated with the introduction and operation of gate processes, and to offer some advice in the context of consumer products.

One of the reasons for writing this series is that much of the literature seems to be more aligned to engineering and technology products than to my interests, which are primarily food and fast-moving consumer goods.

In my first article I defined my scope as “the application of gate process as a key element of product portfolio management, and the process between gates (the stages) as well as the gates themselves.” I gave a brief history of the gate process, the goals and benefits, and a list of issues that are symptomatic of a badly designed or badly implemented process, or are frequently encountered where no gate process exists.

In my second article I commented on the first steps in setting up gate process, or sorting out one that has significant issues: stakeholder engagement; mapping existing processes; project management for the gate process implementation.

In my third article I commented on the design of the stages, and highlighted the importance of flow.

In this article I be shall be covering the control of stages and the design and operation of the gates.

Had you been following the steps in my earlier articles you will now have a flow diagram of the product development process. Gates will be positioned to maximise flow whilst retaining control over critical activities:

- the ones where you want to review outputs;

- the ones you definitely don’t want to start without prior authorisation.

Before moving on to consider the design and operation of the gates, it is necessary to establish their purpose.

The purpose of gates: ‘innovation funnel’ or ‘pipeline’?

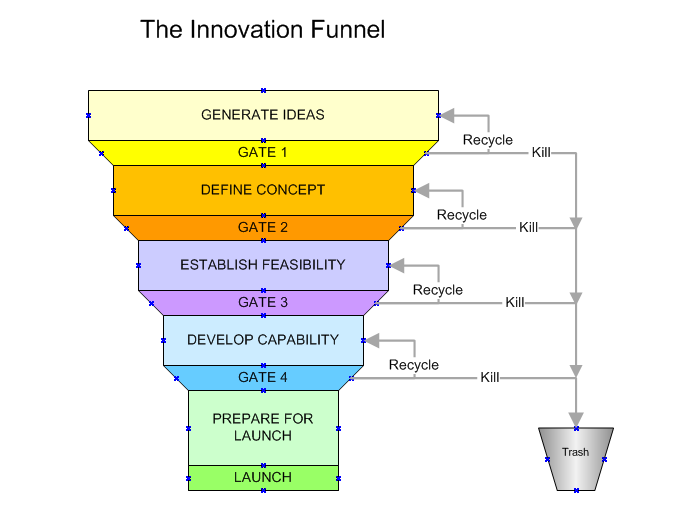

The overall gate process, sometimes called the innovation funnel, is shown in Figure 1. This representation has stage designations for food or fast-moving consumer goods (“fmcg”).

In the past week I have come across two reports on surveys that indicate fmcg and food new product developments have been struggling:

The Grocer: “Only one in five FMCG launches could be considered a success”

Just-food.com: ” Food & drink NPD ‘less successful’ than FMCG peers”

In my experience food and fmcg NPD teams are always under pressure. It seems that there is no shortage of ideas to be pursued. There does, however, seem to be a reluctance to kill projects, which could account for the low success rate of product launches. Existing gate processes often operate as an innovation pipeline rather than an innovation funnel.

Opinion is divided on the most effective approach to innovation. Gate processes are accused of stifling innovation and killing good ideas prematurely. That may well be the case in technology products involving complex and radical developments. For food and fmcg the purpose of the gate process is to ensure:

- Alignment with business strategy

- Project governance

- Portfolio management

- Other benefits, such as reduced time-to-market and effective allocation of resources.

The gate process itself may not guarantee the creation of concepts that appeal to consumers and retailers. Its primary purpose is the early kill of weaker projects so that resources can be focused on those with the greater probability of success. In this context a funnel is more appropriate; only those projects most likely to succeed in the market and contribute to the achievement of business strategic objectives are allowed to progress.

The consequence of ineffective gates (or no gates) is that success is diluted by the misapplication of resources:

- much activity expended on the wrong projects;

- activity on the right projects is pursued in the wrong way, i.e. inefficiently.

I dealt with the pursuit of efficiency last week by designing the stages to maximize flow. The flow diagram, at sub-process level, might look something like the one in Figure 2.

The precise positioning of the gates is going to be determined by the specific nature of the sub-processes and activities, as too are the detailed design of the gates. I shall return later to gate controls impacting on efficiency. First I shall focus on controls to ensure (as far as is possible) the pursuit of the right projects.

On many occasions I have witnessed businesses pursuing projects when the majority of stakeholders believe they are backing a loser. The longer a bad project is pursued, the more investment in time, effort and cost, the bigger the psychological hurdle to overcome in killing the project. So it is really important to be selective, especially in the early stages.

Pursuing the right project: The Rules of Entry

Many fmcg companies have a structured ideas generation process (ideation) run by Marketing. Other product and process development ideas may come from many areas of the business. Ideally all ideas will be registered before submission to Gate 1. Here approval will be granted (or not) authorising the owner to proceed to Stage 1 (Concept/Project Definition) with the relevant functional experts.

A pragmatic approach to restricting the number of ideas going forwards is to create some ‘Rules of Entry’ to the front end of the process. Typically the rules cover three perspectives:

- No qualifying projects are pursued outside the gate process. Qualifying projects might include, for example:

- all changes to products and/or packaging

- all process changes with potential consumer or customer impact

- The gate process is fully adhered to:

- No use of resource without prior approval

- No commitment to customers or 3rd parties (in this example) prior to Gate 4 approval

- Exceptions to (B) limited to capability development capital approved at Gate 3

- Timelines as determined by the gate process

- A prescribed maximum number of active projects

- Only projects meeting prescribed criteria are allowed, thereby eliminating distractions:

- no conflicts with published business strategy

- no non-core products (strategy may, for example, focus on core brands)

- no conflicts with brand or portfolio plans

Once ideas have been filtered by the Rules, they need to be evaluated and prioritised.

The main purpose of Gate 1 is to release a controlled number of ideas to Stage 1 where the product concepts and proposed projects will be fully defined.

The key to achieving maximum throughput and speed to market is to focus the constraining resources on a limited number of active projects. Projects will then be released according to their potential to deliver business benefit. Projects that meet minimum acceptance criteria, released because of a perceived launch deadline, simply fill the funnel with unnecessary noise and obstruct the progress of more profitable projects.

Project prioritisation

At this point (Gate 1) the product concept and project have yet to be defined. Any assessment is likely to be highly subjective. It is at this point that the risk of dismissing good ideas is at its greatest. A balance has to be found between the number of ideas released for project definition (requiring significant resource) and the number rejected without due consideration.

Ideas released to Stage 1 (Concept & Project Definition) can be subject to more rigorous scrutiny. Prioritisation can then be based on 7 criteria:

- Consumer appeal

- Category fit

- Brand Strategy

- Business strategy

- Competitive environment

- Ease and speed of execution

- Scale of likely benefit (At this point profitability is unknown; preparing a business case comes later.)

Consequently, Gate 2 is where the ruthless decisions need to be made. Gate 2 releases projects – only a limited number to be active at any time – ideally a balance between short and long-term projects.

Further release of projects will take place only as active projects are completed (products launched) or killed at subsequent gates. There is also the option to suspend active projects to make way for higher priority new projects, but this is not to be undertaken lightly otherwise agility and speed to market will be compromised.

The Gates

Typically there may be 200-300 activities within the Stages producing 100-150 deliverables controlled by the Gates. Many of these activities and deliverables will be specific to the products or industry sub-sector. I do not intend to go into these in detail but, to summarise the food industry example, the function, inputs and control objectives of each of the gates is as follows:

Gate 1 – Idea Acceptance

Intended to filter ideas to a reasonable number for evaluation.

Inputs: Idea, trigger(s), rationale perhaps driven by market insights, category drivers , manufacturing drivers or procurement drivers.

Controls release of functional expertise to full concept definition, market analysis, project scoping and definition.

Gate 2 – Project Approval

Intended to be the main kill point for unpromising projects.

Inputs: Project prioritisation, product and packaging brief, sourcing plan, market analysis and marketing plan, project/resources plan.

Controls formation of a project team and product development resource to develop the product and packaging concepts, and establish the concept feasibility. This would include development of product and pack samples, and consumer testing.

Gate 3 – Business Case Approval

Intended to be the last kill for internal reasons.

Inputs: full business case, product and pack samples.

Controls release of manufacturing resource for factory trials, capital for plant modifications (where appropriate) and engagement of marketing and design agencies.

Gate 4 – Launch Approval

Intended to be the last kill point for external reasons.

Inputs: Final product specifications and pack designs, commercial forecast and launch plans.

Controls release of designs for reproduction, commercialisation of product and commitments with suppliers.

Gate 5 – Pre-Launch Review and Adjustments

Inputs: changes in plans or expected outcomes following engagement with customers.

Controls release to plan manufacture, supply of materials and packaging and production of product.

Gate 6 – Post-Launch Review (Project Closure)

Inputs: In-market commercial report, issues log and relevant feedback from the business functions.

Controls the release of the project team to pursue other projects.

A further review may be held some months after project closure to determine if the expected benefits have been obtained.

In operating the gates it is important to remember they are one-way. Stage deliverables that fail to meet acceptable standards may be recycled for rework but once ‘signed off’ at the gates these are not to be revisited. (For avoidance of any confusion, please note that planned revisions, e.g. provisional launch plan and final launch plan, are treated as separate deliverables.) Late changes to deliverables that have already been used as inputs for subsequent activities is a major cause of waste and delays.

What next?

The next article in the series will cover some specific industry issues, and systems to support the operation of the gate process.

Related Articles:

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 1

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 2

- How to Implement and Enhance a Gate Process – Part 3

- Overcoming obstacles to successful change programmes