Tony Colwell - 17 November 2011

This article is the fifth in a series on how to avoid the pitfalls of centralised procurement.

In the first article I commented on the reasons why, when many large organisations embark on centralised procurement initiatives with the promise of substantial savings, direct increases in profitability fail to materialize within the business units.

A discussion to capture the views of other procurement professionals has been running at Procurement Professionals Group on LinkedIn.

This week I shall analyze the comments - 157 at time of writing this article - from 65 contributors, excluding myself.

As a piece of qualitative research, the discussion was not intended or designed for quantitative analysis. I have attempted, nevertheless, to identify, normalize and count the reasons for failure mentioned by the 65 contributors. Whilst I accept that the validity of this analysis is questionable, I do feel the results give some valuable insight to the causes of failure, and possible areas to be given attention in order to deliver a successful centrally-led procurement programme.

First I shall comment briefly on the method of analysis.

The initial comment from each contributor was examined and the key reasons identified. Typically contributors gave between one and four reasons. A few contributors gave no reasons in their first comment (for example one contributor's first comment was a question) but did so in their second comment. In such cases the reasons in their second comment were identified. Collectively, I have called these 'original mentions'.

Some contributors posted several comments, restating and clarifying their views. I chose not to count the subsequent mentions of their original reasons. Also, in their later postings, some contributors were debating others' reasons and, again, I chose not to count these mentions.

The reasons were listed and normalized to produce the 16 Reasons listed in Table 1. A few reasons we unclear or ambiguous, so they were categorized as "Other".

Two counts are listed against each of the 16 Reasons. The counts are also expressed as a percentage of their respective totals. The first is the total count of 'original mentions'. The second is a weighted value calculated by attributing to each contributor a total value of 1 shared equally across his/her reasons. For example, if a contributor provided 4 reasons each was given a value of 0.25. The first count gives equal weight to each mention, and the second count equal weight to each contributor.

There are a total of 109 mentions from the 65 contributors.

Table 1

The most frequent reason given for failure of cost savings initiatives to deliver to the bottom line, was Procurement's lack of understanding of the true costs and resultant savings. This was a clear leader followed, some way behind by the next 3 reasons, grouped in close proximity to each other (in order dependent on the number of mentions or weighting by number of contributors).

Poor planning and leadership/unclear objectives covered a range of procurement management-related reasons, including misdirection and inappropriate pursuit of cost reduction where other objectives (e.g. quality or efficiency) were deemed more important. Savings redirected refers to redirection within Business Units or by budget holders, for example where budgets are not adjusted downwards to reflect the procurement savings, or where savings are passed on to customers. Comments relating to savings taken centrally and not passed to BUs or budget holders, for example central rebates, were counted separately. Inadequate stakeholder engagement was the third reason in this following group.

Arguably, lack of stakeholder engagement is a cause of other failures, notably lack of understanding of the true costs, unplanned redirection of savings, delays and non-compliance. Contrary to the results, it is my belief that inadequate stakeholder engagement is the number one reason for failure and that these other causes are symptomatic. The discussion thread gave some support to this hypothesis but the construct of the research provides no means of testing it objectively.

Readers may be interested in the article "7 Essential Elements of Stakeholder Engagement" in which I give a pragmatic guide to ensuring stakeholder engagement in projects and programmes.

Economic factors, e.g. inflation, exchange rates were given as a reason but, arguably, these should be forecast and any losses offset by comparable gains. Failure to forecast was included here rather than in costing inaccuracies.

Inadequate follow through/contract management refers to the disengagement and dissociation of Procurement after setting up the contract. This behaviour might be reinforced by performance measures based on theoretical 'contracted savings' rather than 'realized savings', with non-compliance being a major reason for the difference between the two.

Inadequate sponsorship refers to sponsorship by C-level executives, as distinct from procurement leadership covered in an earlier Reason.

Conflicting metrics and conflicting incentives, and a lack of joined-up KPIs across departments and functions, can encourage non-compliance especially if communications and stakeholder engagement are poor.

Lack of necessary skills refers to the capability of procurement management and staff. We might expect this reason to be understated given that the contributors were mainly from the procurement function.

Optimistic timescales and delays in achieving savings (doing the right things more slowly than planned) were identified separately from other planning and control issues (doing the wrong things) covered in an earlier Reason.

There was a specific reference to contrived savings, or fabrication of results, which was worthy of mention separately from costing inaccuracies.

Finally, the practice of taking savings centrally to withhold them from BUs and budget holders was discussed, and views expressed regarding the adverse effect this may have on relationships with some stakeholders.

I hope that any readers involved in a centrally-led procurement programme will find this analysis helpful as an aid memoire when considering the risks to successful delivery to the bottom line.

Individual comments and the opportunity for readers to post their own comments are available in the discussion "Why do so many procurement cost saving initiatives fail to deliver to the bottom line?" in the Procurement Professionals (Open) Group on LinkedIn.

Tony Colwell - 10 November 2011

In my recent series of articles "Avoiding the Pitfalls of Centralised Procurement" I wrote on the subject of starting a strategic, value-creating procurement programme. Last week I reflected on the

identification of suppliers that will create or add value.

Central to my argument was the need to assess the supplier's capability to collaborate and innovate, to help us optimize existing products/services, and to achieve our desired business outcomes. Rather than focus exclusively on the required product or service we need to pay attention to supplier evaluation and pre-qualification.

This week I shall be commenting in more detail on the methodology for supplier appraisal and how I tailor my approach to meet the requirements of corporations and individual businesses within their specific industry context.

My aim is not to repeat the advice of other guides but rather to suggest to readers that they develop their own approach. Why should we do this when there are 'best practice' templates to follow? Anyone who is familiar with push and pull strategies in supply chain management will understand the advantages of pull strategies when it comes to meeting customer-specific requirements. My point is the supplier appraisal design can be 'pulled' by (external and internal) customer values rather than 'pushed' by generic best practice. Competitive advantage is elusive and uniquely interwoven with the customer values within a supply chain.

Generic templates are fine for generic results. If you are looking for the truly exceptional, then you need a differentiated approach... one tailored to your, and your customers', specific needs.

Here we are looking at supplier evaluation and pre-qualification processes mainly for partnerships. We perhaps need to qualify where partnerships are appropriate. For other types of relationship a generic approach may be more than adequate. To be clear, I am not saying that the design of appraisals for partnerships should be totally new. There will be important elements - for example financial background - which can be taken from generic 'best practice' models. I would encourage appraisers to review and use elements of existing published models and then add criteria appropriate to their specific needs. (I'll come to this later.) Also It helps to know your subject before trying to develop a new approach...

so first I shall recommend a couple of good sources of advice on general practice.

The first source is the Supply Management (CIPS) “Guide to... Supplier Appraisal” - an excellent concise guide to pre- and post-contract appraisal, and a recommended read for anyone new to the subject. It defines supplier appraisal as follows:

"Supplier appraisal is the evaluation and monitoring of supplier capability to ensure successful delivery of commercial outcomes. It is an essential part of strategic sourcing, supplier management and securing competitive advantage."

Whilst it identifies supplier appraisal as essential to securing competitive advantage, the Guide offers no substantive connection between appraisal and the means by which competitive advantage can be secured. The pre-contract appraisal focuses on risk mitigation rather than the identification and exploitation of opportunity:

"Conducting checks – or due diligence – on your potential supplier does not guarantee there won’t be any future problems, but it will help reduce the chance of them arising."

"...an appraisal process is usually used if any, or a combination, of the following contract conditions exist:

• High value;

• Highly complex;

• Long term;

• Business critical;

• Likely to affect reputation;

• International in nature;

• It would be difficult to change suppliers;

• The market has a limited number of suppliers."

My particular interest is in 'business critical' conditions. One needs to be wary of the presumption that Procurement knows exactly what conditions are business critical. While there will be business critical conditions that are apparent to all, there are usually some (especially opportunities) that go unnoticed... and not just by Procurement! These less obvious conditions or opportunities are often the source of competitive advantage. (If they were that obvious then everyone, competitors included, would be addressing them!)

The second source is a research paper "Supplier Evaluation Framework Based on Balanced Scorecard with Integrated Corporate Social Responsibility Perspective" by Worapon Thanaraksakul and Busaba Phruksaphanrat (2009)

The authors developed an evaluation framework from a literature review of 76 papers related to supplier selection criteria. The original evaluation frameworks were conducted in various contexts, and some papers reviewed multiple selection models. From their review, Thanaraksakul and Phruksaphanrat created a generic model - ranking the selection criteria based on frequency of appearance. Given the varied contexts of the original frameworks, individual criteria would have assumed differing importance and been given different weightings. The ranking in the generic model does not take this into account, and I would advise readers not unwittingly to infer that the ranking has any significance to their own circumstances.

I feel I also need to comment on Balanced Scorecard ("BSC"). BSC is ultimately about choosing measures and targets associated with the main activities required to implement a business strategy, not a supplier appraisal tool. (Readers might also consult the EFQM Business Excellence model which is more aligned to achieving excellence through continuous improvement in business processes and management.) BSC aims to provide a 'one size fits all' set of metrics to be cascaded down and across the business, and a balance between the 4 perspectives: Financial; Customer; Internal Business Processes; Learning & Development (5 perspectives if you include Corporate Social Responsibility). The Balanced Scorecard Institute (a private company) acknowledges that these perspectives may not be relevant to non-profit organisations or units within complex organisations, which might have high degrees of internal specialisation. In pursuit of supplier partnerships we may be looking for specialisation and skewed focus i.e. within a particular context, very specifically at certain criteria.

Having criticised BSC for supplier pre-contract appraisal, I can thoroughly recommend Thanaraksakul and Phruksaphanrat's paper as a source of generic supplier appraisal criteria.

As a third source, readers with special interest in quality assurance might look at the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering's

Good Automated Manufacturing Practice Guides. which deal with supplier audits. The assurance demands of automation in this highly regulated industry are particularly challenging, so the GAMP guides are very thorough. The focus on validation planning and supplier due diligence have relevance to answering the question "Is the supplier able to perform?"

The Guides are not cheap, but a quick scan of the contents pages may give a few ideas and help determine if a purchase is worthwhile.

Now I shall address the identification of suppliers that warrant a tailored appraisal, and then the tailoring.

Supply Management proposes the use of Kraljic's Purchasing Portfolio matrix (1983), which plots profit potential against supply vulnerability. The recommendation is to apply the most rigorous appraisals to the high profit potential, high vulnerability quadrant. Most procurement professionals will be familiar with a number of similar 4-quadrant 'supply positioning'models that have been developed subsequently, for example Elliott Shircore & Steele's Procurement Postioning (1985), and Van Weele's Purchasing Portfolio (2000).

'Supply positioning' models convey important concepts but have significant weaknesses in their practical application to supplier appraisal:

• they are intended for purchase items or categories, not suppliers; individual suppliers may therefore span more than one quadrant;

• the supplier's side of the supplier/buyer relationship is disregarded;

• they pose unanswered questions about what will be positioned, at what level of aggregation, and for what organizational unit will the analysis be performed.

In practice, if you perform a portfolio analysis on individual categories you will often identify component groups that map across different quadrants of the grid; then when you look within component groups you may find individual items sit in different quadrants; different mappings are generated with different operating units, and so on. So whilst Kraljic and the like are informative in terms of an overview, they do little to connect specific critical issues and opportunities to supplier capability.

In order to address these issues I've developed my own matrix, based on 'intrinsic value' (as value is what we are ultimately trying to deliver):

- to perform item/category analysis (supply postioning) from an operational perspective

- to link to Value Chain Analysis for the strategic and supplier perspectives.

This enables the use of a common rating/ranking system across strategic and tactical opportunities.

Value Chain Analysis ("VCA") answers the aggregation and organisational questions left unanswered by supply positioning. The point about VCA is that it circumvents the portfolio analysis. VCA will identify critical requirements which cannot be resolved in-house and therefore require solutions to be procured. If VCA does not highlight an opportunity or risk, then the required relationship is probably non-strategic and non-partnership. Note that there may be partnership requirements with the same supplier in other value chains.

(This emphasises the need to perform a strategic analysis before embarking on tactical cost-reduction programmes. See article "Strategic or Tactical Cost-Savings Programme?")

The other things that VCA addresses:

• VCA exposes critical issues and previously unrecognized (or inactive) opportunities,

• within very specific circumstances-within-business-within-industry context... to gain competitive advantage,

• and links these specifically to required supplier inputs.

You will know, beyond the generic requirements, specifically what you are looking for in your key suppliers.

If you have performed VCA you have the information to tailor the supplier evaluation matrix.

Regarding the BSC format, conceptually, the range of criteria is a good: we need to consider all angles. But differentiation - the source of competitive advantage - may be very unbalanced. We may be looking at a focus on specific bottlenecks or opportunities for which the overall scorecard may have little relevance. Additionally, BSC has always been subject to criticism that the content of each perspective is somewhat arbitrary. The focus on defining a simple set of broadly applicable measures conflicts with the requirements for a comprehensive set of criteria both to mitigate supply risks and appraise partnership potential. Arguably, a more comprehensive version can be used for pre-contract appraisal; then a consistent, stripped-down version containing only key performance measures could be used for post-contract review. Personally, I do not like the format for pre-contract appraisal, mainly because I can see a more logical and helpful structure.

My 3-part supplier appraisal separates

(1) Readiness - the physical attributes (requiring action to modify), from

(2) Willingness - the metaphysical (subject to influence, to reasoning and persuasion), and

(3) Ability - the evidential, reasoning material, which indicates the supplier's power or capability to translate the metaphysical into the physical... to realize the dream!

I find this format more conducive to developing a supplier management strategy.

To recap, my appraisal format is in three parts:

Is the supplier ready? Does the supplier have the right infrastructure technology and resources...the appropriate means to provide the products or services you need? Potential suppliers may not have the product or service today, but the capability to provide it. (Perhaps there is a reverse marketing opportunity?)

Is the supplier willing? What are the supplier's values, market orientation, direction and strategy? How flexible and adaptable are they, operationally and commercially? Are you aligned, and will you be a valued customer?

Is the supplier able to do business? Some suppliers may have the right infrastructure, technology and resources; they are focusing on the right market; they express similar values; they say they want your business. The promise is there, but they simply fail to deliver. So, here, we are looking for demonstrable capability to perform.

I am not going further to populate the three categories but I will comment briefly on weighting and scoring.

'Best practice' guides generally refer to weighting the criteria. Preparing and agreeing a weighting system with stakeholders can be a lengthy task. Although I do it, in practice I have never found weighting was necessary; I've never performed a partnership evaluation that came down to the weightings on individual criteria. I do advise that you classify criteria, to be clear what is essential, highly desirable or nice to have.

When it comes to rating, make scores as objective as possible. I like to use a 7-point Likert-type scale: a supplier may have attributes that support or run counter to the achievement of your objectives. A negative score might apply, for example, if a supplier had a strategic relationship with a competitor which would impact adversely on their willingness to support your business.

Finally, the numbers are an aid to stakeholder discussion and agreement. I would never reduce the process to an evaluation by numbers - to a decision based on total score.

I am inviting the views of procurement professionals. and other readers who may wish to comment, at

"

How would you assess a supplier's capability to collaborate and innovate, and to create value in your business?" in the Procurement Professionals (Open) Group on LinkedIn.

Related Items

Readers may also be interested in the discussion "

Why do so many procurement cost saving initiatives fail to deliver to the bottom line?" at Procurement Professionals (Open) Group on LinkedIn.

References and further reading

The Supply Management (CIPS) "Guide to... Supplier Appraisal",

Very similar: "How to appraise suppliers" - CIPS Knowledge Works (available for download on the Chartered Institute of Purchasing & Supply Web Site)

"Supplier Evaluation Framework Based on Balanced Scorecard with Integrated Corporate Social Responsibility Perspective" - Worapon Thanaraksakul and Busaba Phruksaphanrat (2009)

Information on the purpose and application of Balanced Scorecard at The Balanced Scorecard Institute (private company)

"A Study to Compare Relative Importance of Criteria for Supplier Evaluation

in e-Procurement - Ashis Kumar Pani and Arpan Kumar Kar (2007)

Go to top

Tony Colwell - 3 November 2011

In my recent series of articles "Avoiding the Pitfalls of Centralised Procurement" I wrote on the subject of starting a strategic, value-creating procurement programme, and subsequently went on to give

10 tips for the use of Value Chain Analysis.

This week I want to reflect on the identification of suppliers that will create or add value.

My theme for this week was influenced by a recent

video of sales trainer Eric Loftholm in which he talks about the importance of collaboration, innovation and optimisation in the sales process.

When engaging with suppliers of strategic goods or services - repetitive supplies, or one-off purchases that have a continuing maintenance requirement - we can often create value through collaboration, innovation and optimisation. We need to focus on the business outcomes we are trying to achieve not simply on our perceived input requirements. Procurement generally focuses on the required product and, often, not enough on the inherent capabilities of the supplier. We need to assess the supplier's capability to collaborate and innovate, to help us optimize existing products/services, and to achieve our desired business outcomes.

The implications of such 'product' focus in public sector procurement are all too evident. There are many areas (ICT for example) where rapid change can render products and services virtually obsolete by the time they are deployed. Similar failings are less visible in the private sector, where the procurement processes are more agile, and greater flexibility exists to change specifications or source add-ons. But the symptoms are manifest: excessive complexity and fragmentation; cost overruns; supplier margin creep; failing 'partnerships'; suppliers either lacking commitment or gaining a stranglehold over customers.

The answer, I believe, is better supplier evaluation and pre-qualification.

The public sector procurement process mandates that all suppliers are treated equally... the intention is to level the playing field... the outcome is that mediocre suppliers get carried though the process. The process appears to be founded on unreliable assumptions: that there are multiple suppliers who are capable; good suppliers will be keen to supply; their products will be similar and can be evaluated against a single specification.

The reality is this: in the supply of all but the most basic commodities there will be one supplier best placed to meet the customer's needs. Procurement's task is to identify and contract (not necessarily exclusively) with that supplier. This is particularly important in strategic categories, where reverse marketing may also be beneficial. Success cannot be guaranteed by focusing on the product alone. The boundary of the supplier and customer's interactions - the optimum solution - will be determined by the supplier's capability... more precisely, by the supplier and customer's relative capabilities across a broad spectrum of requirements.

So how do we identify the best supplier? How do we evaluate capability?

A former colleague and purchasing manager, Bill Weinert, once said "There are only three questions you need to answer: is the supplier ready, willing, and able to do the business? " It was a great piece of advice that I've taken and developed into a supplier appraisal process. The process is tailored to the specific value creation opportunities within a business, which I'll save for a future blog. For now, I will outline the basic principles.

Is the supplier ready?

Does the supplier have the right infrastructure technology and resources...the appropriate means to provide the products or services you need? Potential suppliers may not have the product or service today, but the capability to provide it. (Perhaps there is a reverse marketing opportunity?)

Is the supplier willing?

What are the supplier's values, market orientation, direction and strategy? How flexible and adaptable are they, operationally and commercially? Are you aligned, and will you be a valued customer?

Is the supplier able to do business?

This is the more difficult of the three questions. Some suppliers may have the right infrastructure, technology and resources; they are focusing on the right market; they express similar values; they say they want your business. The promise is there, but they may still fail to deliver. So, here, we are looking for demonstrable capability to perform.

Conventional supplier audits can tell us a lot: do suppliers have the processes, assurance systems, training, etc. Supplier audits, and procurement due diligence, are usually directed at validating and verifying suppliers' 'readiness', rarely on validating their 'willingness'.

The validation of suppliers' willingness needs to be prospective, not retrospective. Negotiations often play on suppliers' willingness to compromise in order to make a sale; this should not be confused with willingness to perform in the longer term. The key attribute is free will, not the product of coercion. Attempts to gain co-operation by contractual means (obligations and warranties) are not the answer; this amounts to use of force. As I explained last week - in my blog

"Are your Procurement stakeholders champions or saboteurs?"

- force can only guarantee reluctant compliance. And reluctant compliance is not a foundation for collaboration and innovation.

We need to look beyond the conventional audit criteria... to ask "What are this supplier's motivations to collaborate and innovate?" and then, "How do we validate these in our specific context?"

Next week I shall be commenting in more detail on the methodology for supplier appraisal and how I tailor my approach to meet the requirements of corporations and individual businesses within their specific industry context.

In the meantime I am inviting the views of procurement professionals. and other readers who may wish to comment, at

"

How would you assess a supplier's capability to collaborate and innovate, and to create value in your business?" in the Procurement Professionals (Open) Group on LinkedIn.

Related Items

Readers may also be interested in the discussion "

Why do so many procurement cost saving initiatives fail to deliver to the bottom line?" at Procurement Professionals (Open) Group on LinkedIn.

Go to top

Tony Colwell - 21 October 2011

Last week as part of my series on Avoiding the Pitfalls of Centralised Procurement I wrote an article "How to Start a Strategic Value-Added Programme." I commented on the use of Value Chain Analysis ("VCA") which was developed by Harvard strategy guru Michael Porter. In developing VCA, Porter addressed the limitations of his Five Forces model. Whilst Porter's Five Forces model has been taken up extensively by the Procurement community as a strategy development tool, VCA remains little used despite its superior capability.

In this article, I give my tips on the use of VCA in the context of developing procurement strategies. Readers will benefit from prior knowledge or reading on the subject. VCA experts may disagree with my approach - it does deviate from Porter's concept - for which I make no apology. My reasons will become apparent.

First I shall recap on the VCA steps that I outlined in a little more detail last week.

5 steps to developing procurement strategy using Value Chain Analysis:

(1) Create a model of the value chain, setting out the key activities.

(2) Capture external factors and customer values.

(3) Assess the relationship between customer values and key activities. Assess the potential to create differentiation and cost advantage.

(4) Determine operational strategies whereby value to the customer can be most improved, and competitive advantage can be most enhanced and sustained.

(5) Determine procurement strategies to support the operational strategy needs and maximise added value.

Michael Porter said, " In a world where managers are prone to look for simple prescriptions, detailed activity analysis was and is challenging." Value Chain Analysis as prescribed in full by Porter is indeed a challenging and intensive exercise. For our purpose it doesn't need to be.

Here are my 10 tips for running Value Chain Analysis

The first two are suggestions for limiting the scope and simplifying the process:

Tip #1 Be clear on the purpose

If you are using Value Chain Analysis to develop procurement strategy, not as part of a larger programme to formulate business strategy, you are likely to encounter some resistance from other functions. Functional heads may think Procurement is trying to interfere in the formulation of their strategies. Rather than try to re-define business strategy, use VCA as a tool to "listen" to the strategies of other functions. VCA will capture their objectives and how these link, or not, to customer values. This can enable other functions to discover for themselves flaws or holes in their own strategies, and inconsistencies between strategies... also to find new ways of operating, and new ways of using the procurement function to add value.

Tip #2 Limit the scope

VCA examines two sources of competitive advantage: cost leadership and differentiation. If you are not the clear cost leader in your markets, focus on procurement alone is unlikely to achieve that position. The analysis of cost structure is an intensive, numerical process. Use the cross-functional team to focus on opportunities to develop differentiation. Rely on the subjective views of participants: opportunities to create better value-for-money and to take cost out of the value chain will be identified. You can always re-evaluate these later by more objective, numerical analysis.

Purists may argue that these two suggestions deviate from Porters concept. Porter failed to address some of the practical issues of conducting VCA, in particular how to deal with the commercial risk when involving suppliers or customers. Focusing on differentiation rather than cost reduction mitigates the risk; it also lends itself to use of cross-functional workshops, which promote collective ownership.

Tip #3 Reflect on project management methodology and communications

Even if you go for a narrow scope VCA (as suggested above) it is going to touch all areas of the business. You will need appropriate sponsorship and buy-in at senior level, you will need to borrow some key people, and you will gain from communicating to all people who would normally be involved in strategy formulation. You may not be setting out to re-write their strategies but you will be re-writing the way they are supported by procurement; so the strategy makers need to be given the opportunity properly to communicate their strategies. Ultimately, all employees, regardless of their distance from the strategy development process, will need to know what is expected of them but at this stage we are concerned with strategy formulation, not execution.

I am not going to comment on formal project management methodology or advocate its use, but I would suggest that VCA users consider what is appropriate for their circumstances.

Tip #4 Determine the general approach

Value Chains exist at business level, not at corporate level. Businesses may have more than one value chain. This will either be self-evident or will emerge during the VCA session. If evident in advance, you have two options: (i) run entirely separate sessions for each value chain, or (ii) run a session to capture overarching business drivers, issues and objectives, then run separate sessions for each value chain. The advantage of (i) is that participants will be involved in the entire process for the value chain in which they are stakeholders; the disadvantage is that you may be duplicating analysis of similar activities. The advantages of (ii) are that you can engage a broader range of stakeholders (e.g. more senior for the overarching session, more junior for the others) and avoid duplication; the disadvantage is the potential for a disconnect.

Tip #5 Propose the Activity Categories

It helps to have a straw man to take to the first session and to guide your team selection. Aim to use the same categories for all sessions; you may have to make exceptions, but try to avoid unnecessary differences in the models for each value chain. Multiple models will confuse stakeholders and make consolidation of outputs difficult.

Tip #6 Select your team

Ideally all the categories need to be represented. I find workshops are easiest to run with 7 people and become increasingly difficult as numbers increase. So immediately we are looking for a compromise. I once ran a VCA workshop with 22 participants, but would try to keep numbers to 12 or less. You may be able to leave out some or all support activities. You may need to run multiple workshops, for example (a) as suggested in tip #5 above, or (b) separate workshops, one for primary and one for support activities.

There are three important characteristics required of team members. Ideally they will be:

• creative and open-minded. The conservative and critical can have their input later.

• from the same peer group. No individual must be overly dominant, so don't put the MD with junior staff!

• sufficiently senior and established within the business. They need to understand the business and its current direction, and be able to challenge existing strategy. Typically, you would be drawing from BU Executive or the level below. In split sessions - i.e. 4(ii) above - you might draw from 3 levels... no more.

Tip #7 Make sessions easy for participants

VCA sessions are held in cross-functional workshops. I like to run workshops that require no preparation by participants. You will need to do some work on the outputs but that should not require all participants to be present, or put big demands on other stakeholders.

As a piece of practical advice - to minimise digressions into non value-adding activities - my 'rules of engagement' for participants in VCA would include the following definition of a value chain:

• A Value Chain is the chain of activities that add value to a product

• Value exists only where a customer need is satisfied

• Any activity or process that does not serve a customer need is not part of the Value Chain

Tip #8 Separate idea generation from evaluation

The process of working from the customer interface down the primary categories, looking at the impact of customer values, is a fairly logical process but one that should not exclude creative thinking. This is especially important when it comes to identifying opportunities for differentiation and enhancing competitive advantage. Apply 'brainstorming rules' to encourage free thinking: let the ideas flow, then evaluate the ideas after running through all primary categories.

Tip #9 Pay attention to linkages and information flows

Porter highlighted that the linkages between activities and, indeed, vertical links up and down the value chain (including links to suppliers and customers) are a key source of competitive advantage. The key to linking activities together in a way that gives a company an advantage over others is to understand the flow of information that occurs between the various activities.

Tip #10 Involve trading partners with great care

The configuration of activities for competing in a particular way also shapes the appropriate contractual relations with other firms. Exploring the linkages between activities demands the involvement of cross functional teams and possibly the involvement of trading partners. The risk of involving trading partners in VCA sessions is the potential loss of commercial advantage and margin: "the portion of the created value we are capturing" may be lost to the trading partner.

It is safer to leave trading partners outside of initial analysis... until you have sufficient experience and a properly formulated negotiation plan to deal with commercial issues. In most cases it is better not to involve suppliers in the workshops but take specific outputs to them later. VCA might highlight issues, opportunities, or required outcomes; how those issues might be addresses, or the outcomes achieved, would be up for discussion with relevant suppliers.

In introducing VCA last week I wrote "If Procurement has never engaged in such an exercise, Pareto will almost certainly apply: 80% of the benefit from

20% of the effort!" I hope I have encouraged readers to explore the use of VCA for procurement strategy, and that these 10 tips will be of help in developing

a practical approach without too much effort.

Join the discussion, "

Tony Colwell - 14 October 2011

This article is the third in a series on how to avoid the pitfalls of centralised procurement.

In the first article I commented on the reasons why, when

many large organisations embark on centralised procurement initiatives with the promise of substantial savings, direct increases in profitability fail

to materialize within the business units. In my second article I compared strategic

and tactical cost-savings programmes and exposed some of the myths associated with tactical programmes.

A discussion thread

to capture the views of other procurement professionals has been running at Procurement Professionals Group on LinkedIn.

This week I want to touch on the subject of starting a strategic, value-creating procurement programme.

In another Procurement Professionals Group discussion thread,

"Are savings the wrong way to report procurement department performance?"

Bill Young introduced a paper co-authored with Charles H. Green, which provides some interesting insights to the cause of unresolved conflicts between

Procurement and its internal clients, and the reasons why Procurement is often less strategic than it would like to be:

"Procurement today is a complex management service, intended to support the strategic aims of the organisation. However, some of Procurement’s intended

customers are confused about its role and intentions, and hence don’t trust its motives.

"We argue that trust is fundamental and essential in the type of relationship that Procurement is aiming for, but that the metrics and governance used

by Procurement are antithetical to its aims."

I would recommend any reader involved in, or about to set up, centralised procurement to read this paper.

Returning to the discussion I initiated, some observations by contributors have been directed at the need to create value rather save costs:

"Most procurement [departments] are measured on savings - not on value creation,"

"Savings... should leave room for innovation, improved quality, shorter lead times, and not be a bottleneck... [to benefits delivery.]"

"...the same spend with increased revenue, throughput, etc."

"... a truly strategic sourcing group delivers value....."

And the most influential comment, a question:

"What portion of the created value are we capturing?"

This leads me to comment on a technique I like to use to engage stakeholders and identify value-creation opportunities - and a good first step in

developing trust and in determining the strategic objectives of procurement - Value Chain Analysis ("VCA").

The value chain was a concept initially proposed by management consultants McKinsey and later developed and made public in 1985 by Michael Porter in his

book, "Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance". I was fortunate in my earlier corporate career to participate in a joint

supplier/customer VCA programme run by McKinsey. That particular programme was designed to inform and develop marketing strategy for a major

petrochemicals company (the supplier). I took the concept and turned it on its head; now we are using it to inform and develop value-focused procurement

strategies.

Porter's Five Forces and SWOT analysis have become generally accepted tools for the development of procurement category strategies. Despite Porter's

development of VCA as a more relevant tool, I have not seen VCA used by Procurement anywhere other than where we have introduced it. I have seen the

term used, but it has been misinterpreted as cost analysis of suppliers using conventional accounting structures, which VCA is most certainly not.

Michael Porter published Value Chain Analysis in 1985 as a response to criticism that his Five Forces framework lacked an implementation methodology that

bridged the gap between internal capabilities and opportunities in the competitive landscape. Whilst Five Forces and SWOT have their place, properly

deployed VCA is much more rigorous and productive. The Five Forces model applies to all competitors within an industry or market. SWOT provides a simple

framework for individual companies but relies on the user to determine the scope, which leaves the capture of all relevant factors very much to chance. By

contrast VCA provides a tailored and structured framework to identify company-specific strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, and to develop

strategies, within the context of a very specific competitive landscape. This includes vertical links to customers and suppliers... value

creation from procurement and supplier contractual relations.

Whereas Five Forces and SWOT can be conducted by the procurement team, VCA has to be performed by a cross-functional team. This brings substantial benefit

as the cross-functional team members develop shared strategies and a clear understanding of how those strategies both determine and support their individual

objectives.

The value chain allows an organisation to understand what activities it performs, classify them into primary and support activities and most importantly

of all, understand which ones add value to the customer. Porter proposed 9 categories of activities:

- 5 categories of primary activities - inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, services

- 4 categories of support activities (so called because they support the primary activities) - procurement, technology development, human resource management, infrastructure.

These 9 categories can be further subdivided by analysts into their firm's industry-specific and business-specific activities.

Successful use of VCA may challenge Porter's original generic model. I prefer to tailor the value chain at the category level. Despite Porter's claim

that the 9 generic categories exist in every business, they do not work well for some products and many services. For example, in developing a

procurement strategy (unclassified) for military support services (which excluded the procurement of military hardware platforms and associated

dedicated services) we found that Porter's classifications were far from ideal. We defined 6 primary categories: recruiting; basic training, equiping; collective training;

mobilization; deployment. My point is that Porter's classifications are not sacrosanct. The important things to recognize are that the definitions must reflect

business terminology, and the disaggregation of activities must be sufficient to reveal the sources of competitive advantage, whether they be in primary or

support activities.

There are 5 steps to developing procurement strategy using Value Chain Analysis:

(1) Create a model of the value chain, breaking down a market vertical/organisation into its key activities under each of the classifications. Include

upstream links/channels.

(2) Consider the macro-environment, and external factors. What are the factors impacting on the markets and customers? Capture, explicit and implicit customer needs, known customer

values and trends that will affect customer values.

(3) Working from the customer interface down the primary categories, assess the impact of (internal as well as external) customer values. Capture key

objectives and critical success factors within each key activity. Within each key activity assess the potential for enhancing value. Consider points of

differentiation and areas where the business appears to be at a competitive advantage / disadvantage. Capture opportunities to enhance value (and to

defend existing competitive advantage). Move on to consider and capture opportunities to add value through support activities.

(4) Determine operational strategies built around focusing on activities where value to the customer can be most improved, and competitive advantage

can be most enhanced and sustained.

(5) Link opportunities captured in step 3, and strategies in step 4, to procurement activities and to suppliers. Determine procurement strategies to

support the operational strategy needs and maximise added value.

Michael Porter said, " In a world where managers are prone to look for simple prescriptions, detailed activity analysis was and is challenging."

A full analysis of the value chain as set out in "Competitive Advantage" is indeed a challenging and intensive exercise. For our purposes it doesn't

need to be. If Procurement has never engaged in such an exercise, Pareto will almost certainly apply: 80% of the benefit from 20% of the effort!

Next week I shall be giving my tips on running the Value Chain Analysis process.

Join the discussion, "

Tony Colwell - 7 October 2011

This article is the second in a series on how to avoid the pitfalls of centralised procurement. In last week's blog, I commented on the reasons why, when many large

organisations embark on centralised procurement initiatives with the promise of substantial savings, direct increases in profitability fail to materialize

within the business units. A discussion thread

to capture the views of other procurement professionals has been running at Procurement Professionals Group on LinkedIn.

This week I compare strategic and tactical cost-savings programmes and expose some of the myths associated with tactical programmes. I'll also be raising

relevant points captured in the LinkedIn discussion, in particular in connection with adding value rather than simply reducing costs.

The comparison is in the context of a newly formed central procurement organisation. Similar arguments may be made for new programmes run by an

established central organisation, the arguments getting progressively weaker with increasing level of procurement capability maturity.

(Note: beyond level 3 of a 5-level Capability Maturity Model the organisation is operating in strategic, value-adding mode.)

Before going any further it is necessary to make clear that tactical and strategic programmes are, to a large extent, mutually exclusive.

The strategic approach demands portfolio segmentation and the adoption of differentiated approaches for each segment. There are various models for this

(supply positioning for example) and a host of tools and techniques - which I will not go into here - for determining and applying approaches appropriate

to each segment. The tactical programme dispenses with the analysis and segmentation, applying a more uniform approach across all categories, typically

based on supplier rationalisation and leverage.

Later, I will argue that not only are these programmes mutually exclusive, but also the potential to switch from tactical to strategic - and the

potential to gain strategic benefit - is progressively diminished as the tactical programme is pursued.

Moving on to the comparison, first let us consider the typical measurement of procurement cost savings. Savings are usually measured by purchase price

variance for directs, and by similar 'input' measure for indirects. For sake of simplicity, I will refer to these measures collectively as "PPV" measures.

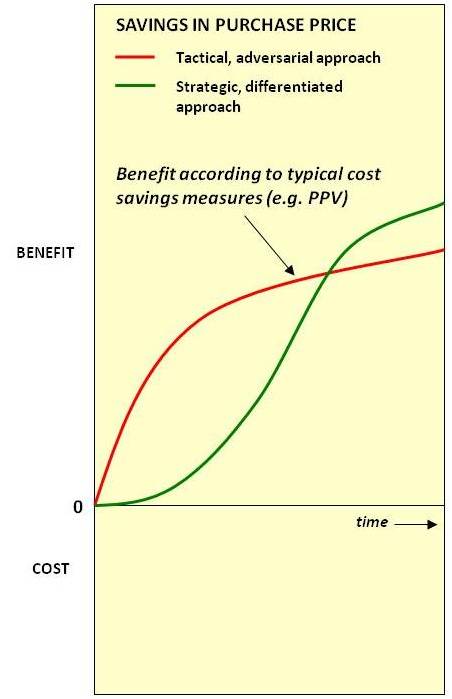

Figure 1 shows the progress of fast tactical and strategic programmes based on PPV measures.

Figure 1

Advocates of tactical cost-savings programmes argue that they achieve quick results. Some Big 4 Consultants and specialist purchasing consultancies run

fast tactical programmes claiming both quick results and that the cumulative savings of a strategic programme rarely catch up with the tactical approach.

Clients may be seduced by this simple message; it's what they want to hear... the promise of quick wins! But the truth is seldom that simple. When I've

made my case, I'll leave readers to speculate as to whether the advocates are proffering a deliberate distortion or whether they are just naive.

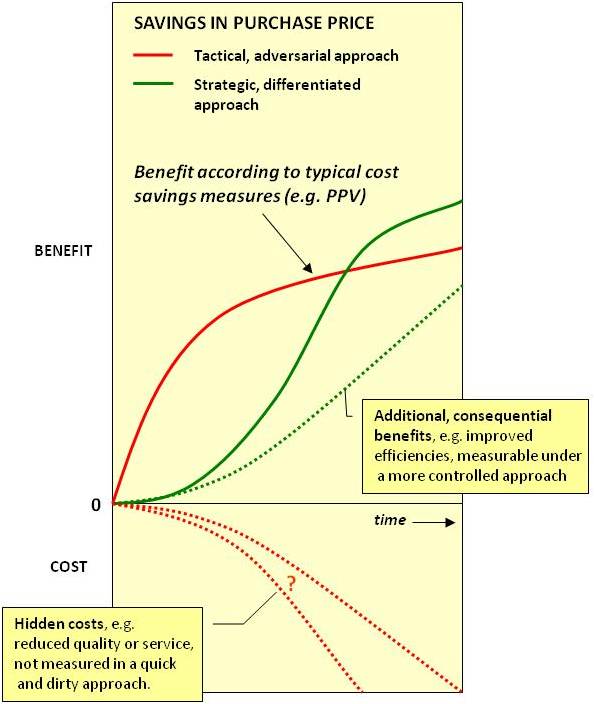

Figure 2 includes the hidden costs of the fast tactical programme and the additional benefits of a strategic programme.

Figure 2

The "hidden costs" are hidden and unquantified because the tactical programme does not allow the time to identify, design and measure how and where

collateral damage will occur. This is one of the main reasons why tactical cost-saving programmes in particular fail to deliver to the bottom line.

Hidden costs might include impact on quality, outputs and waste, as I covered at length last week, or unmanaged risks, for example exposure to insecure

supplies, currency variations, etc.

The additional benefits of a strategic programme come from:

• better stakeholder engagement and use of cross-functional teams

• development of joined-up KPIs and functional targets/incentives

• focus on total cost of ownership,

• risk mitigation across relevant segments/categories

• benefits of supplier partnerships and their innovations

• pursuit of value-adding opportunities

• better analytics

• control of maverick spend

• higher levels of compliance

A strategic programme does not preclude the possibility of pursuing quick wins - just that the approach will be verified and, for a given level of

resource, fewer individual initiatives can be pursued simultaneously than would be possible within a tactical programme.

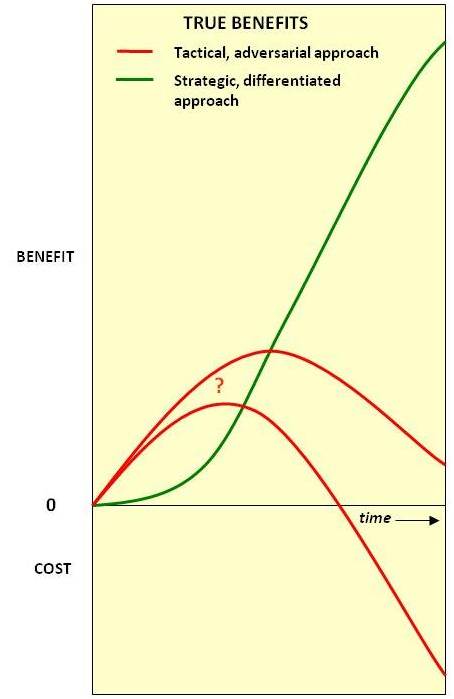

Figure 3 shows the net effect of savings, hidden costs and additional benefits.

Figure 3

Unless an adjustment factor has been applied to PPV, the cumulative net benefit of the tactical programme will be less than PPV predictions. In extreme

cases the 'savings' may actually be negative. Even in the best case, benefits are unlikely to be sustainable; year-on-year improvements become smaller

and it proves impossible to find savings that do not impact in some way on value creation. The cumulative net benefit from the strategic programme will

exceed PPV predictions. The overall effects are twofold:

1. a much greater relative benefit from the strategic approach and

2. an earlier crossover than the advocates of tactical programmes would have you believe.

A well designed and well run strategic programme will deliver sustainable benefits and a greater ROI than a tactical programme.

So, why can't we have the short term benefits of a tactical programme, then switch to a strategic programme for the long-term benefits? Included in the

collateral damage of the tactical programme is the adverse effect on key supplier relationships of inappropriate adversarial and hard-line behaviour:

loss of trust, co-operation and commitment. Adversarial and hard-line approaches are supported by a strategic programme but, because of the analysis and

strategy development, are directed only to appropriate segments of the portfolio. It is this collateral damage that inhibits the switch from a tactical to

a strategic approach. Once supplier trust, co-operation and commitment have been lost they will be difficult, sometimes impossible, to regain.

In my first article, I drew to conclusion as follows:

"Given that many central procurement organisations are founded on the promise of procurement excellence and dubious procurement 'savings' it is clear

that reliable delivery of improved profitability requires systems thinking - an integrated supply chain approach - rather than typical current practice."

To this I would add that procurement best practice is about maximising added value, not necessarily reducing costs.

Acuity (Consultants) Ltd takes a holistic and strategic approach, engaging all key internal (and, where approproate, external) stakeholders to deliver

added value and to ensure procurement initiatives deliver sustainable bottom-line profit improvement.

Join the discussion, "

Tony Colwell - 30 September 2011

Many large organisations embark on centralised procurement initiatives with the promise of substantial savings, yet direct increases in profitability

fail to materialize within the business units.

Judging by the focus of much literature on procurement practice, few organisations would appear to be aiming let alone achieving much higher than

level 3 of a 5-level Procurement Capability Maturity Model. (This subjective view is not materially inconsistent with findings of

research by Batenburg and Versendaal in the Netherlands in 2008.) To explain briefly, the

inference is that Procurement may practise category management, and aspire to achieve lowest total cost of ownership ("TCO"), but would not be looking

at the implications of external integration (e.g. optimising the extended supply chain) and value chain integration (e.g. increasing business value

derived from spend).

Typically targets are set, and 'signed up to', by the procurement department, then savings are identified at the end of each sourcing process and are

reported as a measure of procurement department success. It is generally recognised that savings are only realized as purchases are made on the contract;

responsibility for the delivery of those savings usually falls with the consumers of goods and services. Procurement may monitor compliance - 'realized

savings' vs 'identified savings' or some measure of the uptake of central contracts - and use this as a stick to beat users to make purchases under the

contract when they might otherwise buy elsewhere.

Low compliance may therefore be seen as a measure of errant users rather than ineffective procurement, yet often it is indicative of underlying problems

either with the procurement or execution of the contract. And even when compliance is high, it still does not necessarily deliver equivalent improvements

in profitability. The reasons are in the way 'savings' are measured and the behaviours the particular measures drive.

Procurement savings are usually measured by purchase price variance ("PPV") for directs, and by similar 'input' measure for indirects. The true costs can

only be measured in terms of outputs, after accounting for consequential (in)efficiencies and waste. For capital items, or consumables involving set-up

or maintenance costs, full lifecycle costing - TCO - is necessary. But even TCO has its limitations, focusing on internal costs, ignoring external

factors and value that may derived from the expenditure.

Operational departments and users may have to suffer the consequences of procurement shortcomings long after the sourcing process is concluded.

Procurement KPIs rarely include appropriate measures of downstream, or lifecycle, performance. This inevitably leads to conflicting pressures on the

various stakeholders. In such circumstances, optimum performance, and profitability, may depend on stakeholder relationships and personal integrity

running in opposition to individuals' performance incentives.

Consider a very simple example. Procurement department sources packaging for a new product launch. Say Procurement performance is measured by PPV

relative to target packaging price for the product group. This drives a minimum specification, low-price, high-discount approach... pile it high, buy

it cheap! The Packaging Technologists are interested in protective properties and pack integrity; Production performance is measured on packing line

speeds and minimum waste. Both drive for higher specifications (at higher prices). The stakeholders are in conflict. By changing the performance measure

from 'cost per unit purchased' to 'cost per unit packed' the three stakeholders are more aligned and working to the same ends. Looking further downstream,

one might also measure 'cost per unit sold' (net of credits for damages).

Given that many central procurement organisations are founded on the promise of procurement excellence and dubious procurement 'savings' it is clear that

reliable delivery of improved profitability requires systems thinking - an integrated supply chain approach - rather than typical current practice.

Acuity (Consultants) Ltd takes a holistic approach, engaging all key internal (and, where approproate, external) stakeholders to deliver added value and to ensure procurement initiatives deliver bottom-line profit improvement.

This article is the first in a series on how to avoid the pitfalls of centralised procurement. Next week I look at strategic vs tactical cost-saving programmes.

Join the discussion, "Why do so many procurement cost saving initiatives fail to deliver to the bottom line?" at Procurement Professionals (#1 supply chain & sourcing group) on LinkedIn

References:

"Maturity Matters: Performance Determinants of the Procurement Function", R Batenburg & J Versendaal, Utrecht University 2008.

Go to top

Tony Colwell - 23 September 2011

In the last week the media have reported huge waste of UK public funds associated with shared services projects. This triggered broader debate

about the value of public sector projects.

Critics frequently refer to the failure to control suppliers of services - the consultancy architects of shared services; technology suppliers;

outsourced services providers - and the hidden legacy of debt from PFI projects.

The problem is not confined to the public sector. In a recent

live discussion

hosted by The Guardian, it was claimed that research in the private sector shows 70% of shared services and mergers fail to deliver to expectations,

and that the problems are not about processes, they relate to people, power and politics.

Cranfield University estimates for many firms, up to 75% of the products and services they provide are sourced from suppliers, suggesting that

relationships between firms are a key source of competitive advantage as opposed to the focus on managing processes and physical assets.

Sustainable competitive advantage requires agreement to operate on terms where neither partner can exploit the other.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that public sector procurement processes and the resultant contracts for services are failing to provide adequate protection.

In my experience, private sector contracts frequently have similar shortcomings. Legal advisors often focus on documenting current requirements -

a kind of snapshot - rather than considering how the requirements and relationships might evolve.

Service agreements need to provide a dynamic framework for controlling the evolving commercial relationship over the contract life cycle.

Otherwise, as requirements and services digress from the original scope and intent, the result will be costly and uncompetitive add-ons, and margin

creep generally in the supplier's favour.

So, here are 3 guiding principles to ensuring enduring competitive service:

1. Procurement must focus on determining, and contracting on the basis of, supplier capability, not on lowest cost or perceived best value

of current, soon-to-be-obsolete solutions. Selection criteria need to take account of suppliers' intrinsic strengths and weaknesses:

(a) infrastructure, resources and technology;

(b) alignment and strategy;

(c) assurance systems and demonstrable ability.

2. Contract in a way that prevents suppliers from exploiting and profiting excessively from changing requirements. Contract provisions

must include

(a) change control procedures to deal with any significant changes - in the business, the requirements, the assets and resources deployed,

the methods of providing the services - and to set the costs or budget for modified services. The procedures must permit customer discretion in

determining the way forward, including the use of third parties if the incumbent supplier is uncompetitive.

(b) supplier obligation not unreasonably to refuse to perform similar services to protect against 'cherry picking' or attempts to frustrate

the development of services;

(c) benchmarking to establish continuing competitiveness, both in terms of cost and good practice. The intention is to protect against

- divergence in customer's requirement and supplier's capability

- drift caused by cumulative effect of small changes

- uncompetitive pricing for changes.

(d) termination provisions on grounds of service and cost – in whole or in part, to allow the separation of services for which the

supplier is no longer suitable.

3. Manage supplier performance. A service level agreement should include a formal, documented process comprising:

(a) responsibilities matrix;

(b) key performance measures and reporting cycles;

(c) incentives to balance cost and service;

(d) contractual cost targets at contract start, as modified under change control and benchmarking;

(e) contractual service levels reflecting industry good practice, as modified by change control and benchmarking.

If your chosen supplier is reluctant to co-operate in any of the above, you have to ask, "Have I found the best supplier?" If customer and supplier

are confident that the supplier is the best placed to provide the service, then reaching agreement in these areas should be possible.

Discussion at Procurement in UK Public Sector Group on LinkedIn

Tony Colwell - 16 September 2011

After the lull of the holiday season the Interim Management community has shown renewed interest in subject of "Catch 22" - the Cabinet Office's

constraints on public sector deployment of Interim Managers. A discussion thread has restarted in the

Odgers Interim Management Group on LinkedIn.

The discussion had turned negative and a new direction, leading to some positive action, was called for. Because this is a closed Group,

I thought it would be appropriate to reproduce my comment, which (with minor editing) was as follows.

This [Odgers Interim Management] discussion thread started on 3rd June. Alf Oldman and I had a meeting with the Cabinet Office on 1 July at which we

were informed of plans to introduce new framework agreements to cover consultancy and executive interim requirements. We were not bound by non-disclosure

agreement; it is more out of regard for our professional integrity that we have not broadcast plans that the Cabinet Office has chosen not to announce

formally. It might be helpful, to take the debate forward in a constructive manner, to disclose some of what we know.

The meeting dispelled a few myths surrounding "Catch 22".

The Cabinet Office constraints on the use of 'consultants' applied to Central Government only. The use of consultants and interims by local authorities

has been affected by budgetary constraints, not (as far as I am aware) by Central Government directive.

William Jordan, former head of OGC, mandated that Central Government departments choose from 3 pre-existing models:

1. DWP Cipher - the outsourced Capita supply model;

2. Internal Buying Hub (CIX)/Home Office portal to Buying Solutions' frameworks.

3. ANY OTHER OPTION OFFERING EQUIVALENT VALUE.

The mandate required that any exceptions valued at more than £20k (but less than the £100k threshold requirement for tendering via OJEU) be supported

by a business case approved by the department head, and the Cabinet Office notified. I am not clear it was mandated that the Cabinet Office would have

to approve such business cases. Besides, the freedom to use "any other option" gives enormous scope, especially in light of the

Public Accounts Committee's findings that the

Cabinet Office is incapable of assessing value.

Cabinet Office (and formerly Buying Solutions') frameworks - of which there are currently 19 active - have never been mandated, and neither will they be.

That the Cabinet Office should be seen to prevent Central Government departments, or local authorities, from discharging their responsibilities is

clearly unwise both politically and in terms of maintaining managerial accountability.

The proposed new frameworks are to fall within two distinct categories: (1) contingent labour; (2) consultancy, INCLUDING EXECUTIVE INTERIM.

Executive interim will not be classified as contingent labour, but 'handle-turning' contractors' roles will be. I feel it is inappropriate to comment

on the dividing line in terms of day rates but it was clear to me that many existing public sector 'interims' will fall into the contingent labour

category, including those working at rates above recognised as lower-limit thresholds by the two professional bodies, API and IIM. This is to be welcomed.

If the Cabinet Office delivers what Alf and I were told is planned, then the recognition of executive interim status and the crossover with,

and alternative to, big consultancy will be addressed.

My focus since the meeting has been on the interim management supply model. The success of any new frameworks is entirely dependent on the outcome of

the tendering process. The critical factors are (a) Cabinet Office recognition that best value does not equate to lowest Interim Service Provider's ("ISP") margin, and

(b) ISP's placing bids that demonstrate, can deliver, and can measure the added value of a higher-margin service.

The Cabinet Office is fully aware of the need to evaluate different interim management supply models. To this end Alf and I produced a second White Paper

which we have not published (in the public domain). Much of the content regarding measuring the effectiveness of interim management supply models has

been put to the IM community for discussion, both before and after we submitted the White Paper to the Cabinet Office. Details can be found in

my earlier blog.

I also started discussions in the most active ISP's own Groups - including a discussion at Odgers Interim LI Group -

to ensure that ISPs as well as the broader Interim community were aware of the need to develop innovative models . Disappointingly, these attracted

only moderate interest and little comment from the ISPs themselves.

Alf and I know from private discussions we had with various ISPs that more is going on behind the scenes than is apparent in the public domain.

I would expect some reticence to discuss publically what ISPs might be doing to establish their own positions and place their bids. The future of

the executive interim opportunity in Central Government departments is at stake. So perhaps this discussion should be redirected towards ensuring

that ISPs provide the type of interim supply model that we executive interims would wish.

Non-members of the Odgers Interim Management Group can join the discussion

"Effectiveness of Interim Management Supply Models – Where Next?" at API (open) Group on LinkedIn

Tony Colwell - 19 August 2011

Stakeholder engagement is a critical factor in the success of business change, especially business transformations, which may require significant cultural change.

Business transformation typically involves people, process and systems changes which need to be delivered in order to produce a step change within the business.

The design of effective processes and application of appropriate technology is not enough to ensure success. Insufficient acceptance and adoption of the new processes,

arising from inadequate engagement of stakeholders, is a common cause of transformation failures.

The same is true for public sector transformation, whether internally within public and civil organisations or in pursuit of broader civil and social reforms.

Much of the published literature on stakeholder engagement deals with the introduction of sustainable engagement programmes in public,

private and civil society organisations - with strong emphasis on accountability, particularly democratic accountability - and is applicable

to the integration of stakeholder engagement with corporate governance, strategy and operations. Readers who are interested in this context

might consult The AA1000 Stakeholder Engagement Standard.

This article is directed at the tactical application of stakeholder engagement within a specific project or programme - a pragmatic approach

to getting stakeholders on board, and ensuring the desired outcomes are achieved.

The overall aim of the engagement process is to achieve the desired outcomes. The desired outcomes should, therefore, always be at the forefront of planning an engagement process.

They need to be clearly stated - setting out exactly what is sought from the proposed changes in process, technology, etc.

The delivery of the technology, the process and the process outputs themselves are not the main focus, which must be on the achievement of the outcomes.

This enables some latitude in determining how the outcomes are achieved - what technology, process and process outputs are used -

so that stakeholders have a sense of purpose.

To engage stakeholders fully there are 7 areas we address. It is important to note that these are not sequential steps,

although the emphasis moves, with the passage of time, from the lower to the higher-numbered items in the following list :

1. Sponsorship: Ensuring sponsorship for the change - in business, at a senior executive level from both internal

‘supplier’ and ‘customer’ perspectives - in public life, from institutional heads representing providers and receivers of services. Often,

work needs to be done in advance to define the scope and context of the engagement in order to gain commitment to the engagement programme.

2. Involvement: Involving the right people in the design and implementation of changes, to make sure the right changes are made

- so ensuring their effectiveness. Also that no stakeholder group is inadvertently or intentionally excluded - so ensuring legitimacy.

And, at the outset, involving the right people in the design of the engagement plan itself.

Seek active participation. Consultation is good but programmes where the delliverables are 'done to' or 'done for' the stakeholders are

less likely to lead to successful outcome than if they are (in part) 'done by' stakeholders.

3. Impact: Assessing and addressing how the changes will affect people. 'Sweeping issues under the carpet' is a

frequent cause of failure, yet often the issues present an opportunity to increase stakeholder engagement, by getting them to participate in

finding or developing solutions.

4. Communication: Telling everyone who's affected about the changes... and listening. Early communication the context

in which the stakeholder engagement is taking place is important: - for sponsors, a common understanding of context and purpose ensures consistent

leadership; - for other stakeholders to align participants, clarify their roles, and ensure the process is responsive to their needs.

5. Readiness: Getting people ready for the changes, by ensuring they have the right information, training and help.

The timing and resources required are often underestimated but the requirements can be reduced by the planned involvement of key stakeholders.

6. Responsibilities: Ensuring people understand and accept their responsibilities, and are held accountable.

Unambiguous definition of participants' roles is a pre-requisite.

7. Compliance: Addressing resistance; in most cases revisiting 1-6 above, but occasionally requiring the removal of

negative influences. Former US Secretary of State, Colin Powell said "The good followers know who the bad followers are, and they are waiting

for you to do something about it." I agree. However, the necessity to remove a significant number of negative people usually indicates a

failure in design, planning or management. Mass removal of protesters, and their replacement by sycophants, is a recipe for disaster.

This is not an exclusive list. Additional political and organisational issues will need attention, depending on the nature of the changes.

I opened by saying that stakeholder engagement is a critical factor in the success of business change. It seems to have become

fashionable to put stakeholder engagement at the pinnacle of the business change agenda - suggesting that change management is purely about

stakeholder engagement - as if changing the organisation and improving stakeholder engagement will somehow transform the business.

Real business change is not achieved by changing the organisation structure. Effective process is a pre-requisite.

W. Edwards Deming said "If you can't describe what you are doing as a process, you don't know what you are doing" (engaged or not).

Stakeholder engagement helps the design of good processes, ensures their effective operation, and encourages personal commitments to

deliver desired outcomes.

Further reading:

Tony Colwell - 11 July 2011

Following on from my last blog, “Effectiveness of Interim Supply Models – The Metrics?”

and a recent invitation to apply for an interim assignment with a not-for-profit organisation, I want to explore the valuation of consultancy and interim assignment outputs.

The link between my blog and the invitation is the critical significance of the brief or Statement of Requirements (“SoR”).

I have concerns over the absence of references to desired outcomes. My concerns are not specific to public and not-for-profit sectors so, hopefully,

my comments will be of interest also to readers from the private sector.

“The Effectiveness of Interim Supply Models” followed a visit to the Cabinet Office with my colleague, Dr Alf Oldman,

and numerous conversations we had with fellow interims and interim service providers, and is a precursor to our joint submission to the Cabinet Office.

The invitation to the Cabinet Office had come indirectly from the Rt. Hon. Francis Maude, Minister for the Cabinet Office & Paymaster General, following receipt of

Dr Oldman’s Catch 22 White Paper.

Francis Maude replied,

“To ensure value is both improved and sustained, work is currently underway to develop a new strategy to centralize and

simplify how Departments buy common types of consultancy and contingent labour.”

Alf Oldman gives his account of the meeting and in his latest blog considers “

Reforming the Professional Interim and Independent Consultant Supply Chain Model?”

I shall pursue a particular perspective, relative to my focus on supply chain management: measuring the delivery.

But, first, it is necessary to explain the context of the meeting, which I shall do by reproducing two paragraphs from Alf Oldman’s blog,

in which Alf refers to the House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts report entitled

“Central government’s use of consultants and interims”

(“the PAC report”):

“Francis Maude kindly forwarded a copy of my White Paper to the appropriate team at the Cabinet Office and invited me to speak with the official leading the team and

this resulted in a very successful meeting last Friday. I was accompanied by Tony Colwell who is a Supply Chain expert.

“I met with Tony ahead of our visit to the Cabinet Office and kicked around our views of the professional interim supply model.

This resulted in the schematic entitled the “Professional Interim Community“

which we used as a discussion aid at the Cabinet Office – this contains five archetype models of intermediary.

The meeting went very well and we had a good exchange of views and were able to empathize with each others’ perspectives.

In passing, the PAC report was mentioned as evidence confirming both the importance and dependence of Central Government on consultants and interims

for the foreseeable future. I strongly encourage the reader to take some time and read the PAC report carefully, in particular the evidence provided by